Iron deficiency anemia is "when body stores of iron drop too low to support normal red blood cell (RBC) production" (Harper). It is "the most prevalent single deficiency state on a worldwide basis" (Harper). This could occur as a result of "inadequate dietary iron, impaired iron absorption, bleeding, or loss of body iron in the urine" (Harper).

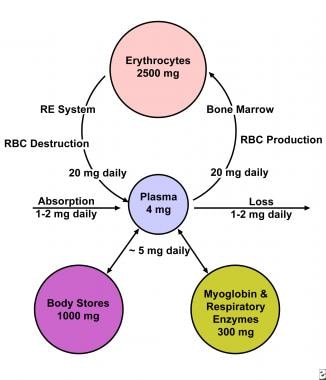

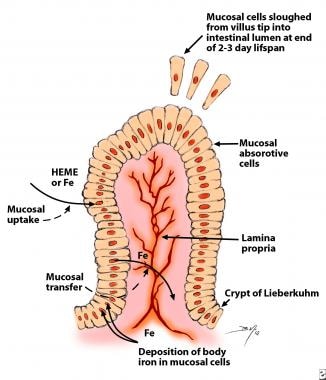

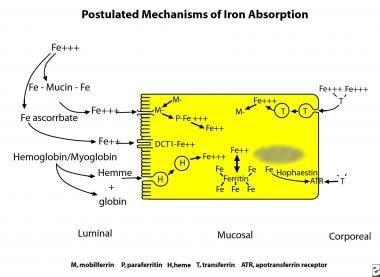

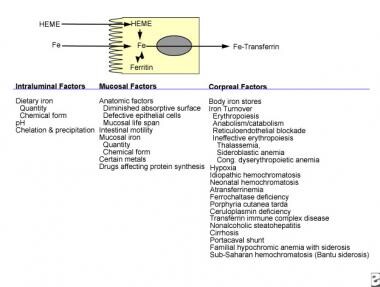

Iron is important for the body because it helps complete metabolic processes like "oxygen transport, DNA synthesis, and electron transport" (Harper). There are three separate pathways for iron uptake in the small intestine which include a "heme pathway and 2 distinct pathways for ferric and ferrous iron" (Harper). The absorption of heme and non-heme iron is noncompetitive. In healthy bodies, iron absorption is regulated by absorptive cells in the small intestine that balance the amount of iron absorbed with the amount of iron lost. However, when either the body begins to lose iron too quickly or doesn't take in enough digestible iron, this balance can be offset, causing iron deficiency anemia (Harper).

One of the most common reasons for a lack of iron in the diet of people with iron deficiency anemia is limited access to meat (Harper). Another common reason is hemorrhage, where a person loses a significant amount of blood suddenly. The body responds by activating the bone marrow to create new hemoglobin to replace the lost blood, thus depleting the iron supply in the body. Other causes include hemosiderinuria, hemoglobinuria, and pulmonary hemosiderosis, all different forms of blood in the urine. Additionally, eating starch or clay, extensive surgery on the small bowel, and disease (like celiac disease) can all contribute to the development of iron deficiency anemia (Harper).

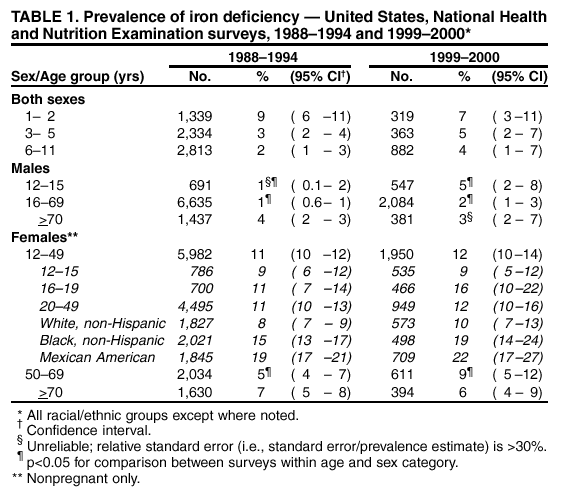

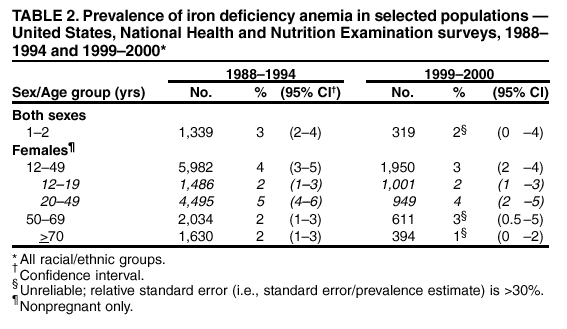

Generally, anemia is more common in areas with diets low in meat. These places all have a higher amount of intestinal parasites, like hookworms, that result in GI tract blood loss. In countries like the U.S., where this is less of a problem, the main demographics affected are pregnant women and people that have suffered from hemorrhage. In general, children and particularly infants (especially those on cow milk diets instead of breastmilk) are at a higher risk to develop iron deficiency anemia. Between men and women, women are much more at risk to develop anemia. During pregnancy, a woman loses 500 mg of iron. During each menstruation cycle, a woman can lose 4-100 g of iron. In comparison, men only lose 1 mg per day during natural losses like sloughing epithelia and secretions from the skin. Because of women's extra losses, and the fact that they eat less than men, their bodies need to be nearly twice as effective at absorbing iron than men's systems. This makes it very important to recognize when women are becoming anemic, especially during pregnancy and during early development. Race has little affect on the appearance of iron deficiency anemia demographically (Harper).

The symptoms of iron deficiency anemia include fatigue, leg cramps, and general lack of strength. In children, it can lead to slower growth and development. Although not life threatening in itself, if left untreated, it can lead to the development of pulmonary and cardiovascular disorders that can be life threatening (Harper).

Iron deficiency anemia is easily treated with iron dietary supplements and diet changes. Some options may be prescribed to treat the causes of the anemia as well, like oral contraceptives to lighten menstruation flow, antibiotics to treat ulcers, or surgery to fix bleeding (especially in GI tract) (Clinic). Iron deficiency anemia can be prevented by eating iron rich foods, like red meat, beans, and dark leafy vegetables. It also helps to eat foods rich in Vitamin C, which increases iron absorption, like oranges, broccoli, and kiwi. Finally, breast feeding infants or feeding them iron fortified formula is the best way to avoid anemia (Clinic).

Works Cited:

Harper, J. (n.d.). Iron Deficiency Anemia. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/202333-overview#a7

Clinic, M. (n.d.). Iron deficiency anemia. Retrieved September 14, 2015, from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/iron-deficiency-anemia/basics/treatment/con-20019327

(Treating)

(Treating) (11 Reasons)

(11 Reasons) (Harper)

(Harper)

(Harper).

(Harper). (Harper).

(Harper).